Old Books and the Passage of Time

I recently got a couple books that I’ve had on my “to read” list for several years: Frank Abagnale’s The Art of the Steal and Joseph Heath’s Enlightenment 2.0. And I’ve been enjoying both books, but they’re both surprisingly dated. I keep being aware of how old they are, sometimes in ways that really catch me off guard.

The Art of the Steal

The anachronisms in the Abagnale book are more dramatic, in part because the book is older (from 2001), and in part because Abagnale is more of a sensationalist to begin with. (It seems a lot of the claims he made about his most impressive capers are less than accurate—which makes sense coming from a successful con man!)

He takes pains to explain cutting-edge technology, like color scanners and laser printers. Then he warns about people using them to forge store gift certificates, when I’m not sure I’ve seen an actual printed gift certificate (as opposed to a gift card) in years. He talks about scanning and printing near-perfect replicas of US currency, which is no longer possible. He describes the exciting new security features in the redesign of the twenty-dollar bill, which I just barely remember being introduced.

But the most jarring bits are in his first real chapter, about check forgery. Partly, again, the technology has gotten better. He complains that many companies print checks on “that familiar blue or green basketweave check paper” you can buy at any office supply store. But it’s not really familiar to me! Instead I just take for granted that all checks have the fancy new security features he’s advocating.

But moreover, he’s amazed that stores accept checks without checking the signature—whereas I’m amazed that stores accept checks at all! He raises the possibility of paper checks dying out, only to dismiss it:

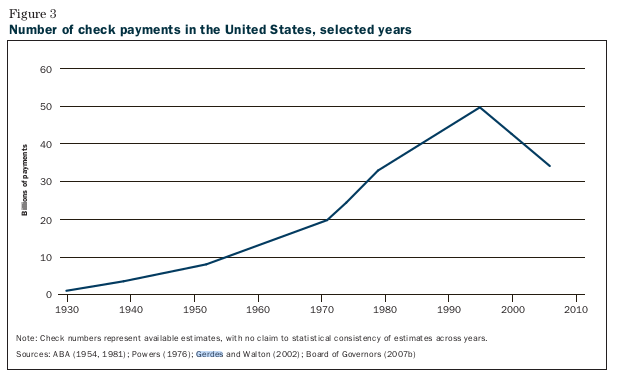

I’ll be long dead, even if I live to a ripe old age, before checks will ever disappear. The amount of checks we write is growing at a rate of more than a billion checks a year. So they’re not even declining in use. They’re growing. I remember fifteen years ago, when we were writing 40 billion checks a year, people said it would never reach 50 billion, and now we’re at almost 70 billion. People happen to like checks. They’re familiar. Many consumers will say, “I like this check. It has some float to it. I like that much better than when the bank immediately goes into my checking account and takes the money out. I also like the idea that I can get the check back and see who I wrote it to and have a record of it.” And we have a very large generation that is not comfortable with smart cards and electronics. They’re leery of new ways of payments, and they don’t fully grasp them.

Electronic banking is still much more of an unknown frontier. And there’s no forgetting the billions of dollars that banks have invested in electronic readers, sorters, and other check processing equipment. We’re not going to just scrap it and plow money into home banking. There are banks out there pushing electronics, but there are a lot of other banks that would just as soon stay with checks.

And that’s all very convincing, except for one thing:

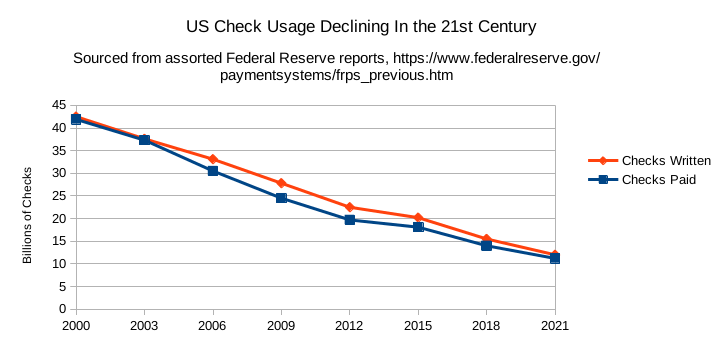

Data collected from https://www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/frps_previous.htm

Data collected from https://www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/frps_previous.htm

I can’t explain the discrepancy between Abagnale’s numbers and the Fed’s. Abagnale doesn’t cite a source, and while the Fed is pretty clear that its numbers aren’t totally solid, I know I trust them more. But it sure looks like The Art of the Steal was written at nearly the exact peak of US check-writing. The book is confidently asserting that checks would never fade—to a present-day audience which knows they’re well on their way out.1

Enlightenment 2.0

Joseph Heath wrote a much more serious book, and a much better researched one. It’s also much more recent, from just 2014. But that makes the anachronisms more disconcerting.

The first thing that really surprised me is his discussion of computer chess. Heath argues (correctly!) that people don’t think in a purely linear, logical-deductive manner, but instead rely on a lot of shortcuts and heuristics. He illustrates the difference by contrasting the human approach to chess-playing with the approach of chess computers like Deep Blue. Computers, he explains, are analyzing millions of branches of the chess decision tree; in contrast, human grandmasters rely on “a heuristic pruning of the decision tree, guided by an intuitive sense of what seem to be the most promising moves or of what sort of position they want on the board.” He goes on to observe that

[N]o one is able to articulate how this initial pruning is done. It is all based on “feel.” … To this day, no one has ever succeeded in reproducing the intuitive style of thinking in a computer, simply because we don’t know how it is done (despite the fact that we ourselves do it)…. The fact that this much computing power can be deployed without yet achieving the “final, generally accepted, victory over the human”22 is a monument to the power and sophistication of nonrational thought processes in the human mind.

Three years later, Google unveiled the AlphaZero engine, which uses modern machine learning techniques to do heuristic pruning very similar to what humans do, and avoids the need to crunch through the entire decision tree. To the best of my knowledge, every top chess program now uses these neural network-based heuristics.

I don’t bring this up to criticize Heath. He was correct when he was writing; and his main point is still correct, since he was mostly trying to explain how human thought works, not how to write a chess program. But it’s definitely a moment where I paused and was thrown out of the argument, because my first reaction was “but that isn’t true!” With a belated followup of “…any more”.

Anachronistic Politics

But there’s another bit that seems far more jarring and anachronistic today, even though it also seems prescient. Heath writes as an unapologetic liberal2, and his project is to build a modern, renewed liberal politics. So he sets the stage for his argument by discussing some of the problems he sees in the modern Republican party.

The big tent of the American right has always sheltered its share of crazies… There came a point, however, when the sideshow began to take over center stage. Americans woke up to find that their political system was increasingly divided, not between right and left, but between crazy and non-crazy. And what’s more, the crazies seemed be gaining the upper hand.

He later observes that the American right “always seem to be very angry”, and that

there has also been a significant rise in the amount of bullshit. Lying for political advantage, of course, is as old as the hills. What has changed is that politicians used to worry about getting caught.

He is, of course, describing the 2012 campaign that pitted Mitt Romney against Rick Santorum in the primary and Barack Obama in the general election.

Ten years later, I’m not sure whether to read Heath’s writing as prescient or naive. He forecast the shape of Trumpian politics nearly perfectly, so in that sense he was clearly on to something. But it’s disconcerting to remember a time when we might have viewed Romney and Santorum as shockingly out-of-bounds artists of bullshit.

So those are two different books I’m reading, which both aged surprisingly quickly. I don’t have any grand takeaways from this, or anything. But it’s interesting to see just how unpredictable trends can be. Sometimes they keep going much further than you think they can. And other times, when they seem like they’ll last forever, they stop almost without warning.

What else has aged surprisingly quickly—or surprisingly well? Tweet me @ProfJayDaigle, BlueSky me @profjaydaigle.bsky.social, or leave a comment below.

-

In Abagnale’s defense, he only claims they won’t disappear, and indeed they haven’t. But the dynamics of check-cashing today are radically different from the dynamics he describes, and his prediction that banks will keep avoiding electronic banking seems particularly off the mark.

In Abagnale’s offense, he has a comment a few chapters later that his children don’t like writing checks and he thinks it’s a generational thing. So he could have seen it coming. ↵Return to Post

-

In both senses of the term; he opposes the political right, but he also isn’t a leftist. ↵Return to Post

Tags: data books

Support my writing at Ko-Fi

Support my writing at Ko-Fi